5.1 Newton’s laws of motion

Isaac Newton unified Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion (discussed in Chapter 3) with Galileo Galilei’s theory of falling bodies (discussed in Chapter 4). Newton published his laws of motion and universal gravitation in The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, commonly known as the Principia, in 1687.[1]

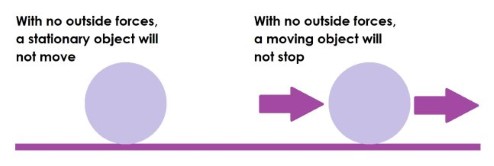

5.1.1 Newton’s first law

Newton’s first law of motion states that objects continue to move in a state of constant velocity, which can be zero, unless acted upon by an external force. The tendency of an object to resist a change in motion is known as inertia, and objects that are moving at a constant velocity are said to be in an inertial reference frame.

Figure 5.1 |

Newton’s first law. |

Galileo had first suggested this law, but it had not been universally accepted because it contradicted Aristotle’s laws of physics.

5.1.2 Newton’s second law

Newton’s second law shows how an object will be affected if an external force does act upon it. This law states that the rate of change of momentum of a body is proportional to the resultant force acting on it, and will be in the same direction. This means,

| F = ΔpΔt | (5.1) |

Δp = mΔv, and a = ΔvΔt, and so Newton’s second law can be re-written as

| F = ma | (5.2) |

Here, F is force, Δ can be read as ‘change in’, p is momentum, t is time, m is mass, v is velocity, and a is acceleration. This shows that less force is needed to push something lighter, which means that less massive objects have less inertia. More force is needed to push something heavier, and so more massive objects have more inertia.

Figure 5.2 |

Newton’s second law. |

5.1.3 Newton’s third law

Newton’s third law states that the force on an object is always due to another object; all forces act in pairs that are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. This is why you feel recoil when you strike an object, and why you do not fall through the Earth due to the pull of gravity.

Figure 5.3 |

Newton’s third law. |

5.1.4 The conservation of momentum

The combination of Newton’s second and third laws shows that momentum must be conserved (as discussed in Chapter 4). This means that the total momentum of two objects remains the same before and after a collision.

| If F = ΔpΔt and F = -F, then Δp = -Δp. | (5.3) |

5.2 Newton’s law of universal gravitation

Newton’s law of universal gravitation states that every mass attracts every other mass in the universe, and the gravitational force between two bodies is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Spherical objects like planets and stars act as if all of their mass is concentrated at their centre, and so the distance between objects should include their radius.

Figure 5.4 |

Newton’s law of universal gravitation. |

| F1 = F2 = Gm1m2r2 | (5.4) |

Here, for two objects that are orbiting a common centre of mass (like the Earth and the Sun), m1 is the mass of the less massive object (like the Earth) and m2 is the mass of the more massive object (like the Sun). F1 is the gravitational force produced by m1, and F2 is the gravitational force produced by m2. r is the distance between the two masses. Finally, G is a constant that is the same for everything in the universe.

Newton stated that the force of gravity is always attractive, works instantaneously at a distance, and has an infinite range. Most importantly, it affects everything with mass - and has nothing to do with an object’s charge or chemical composition.

This means that it can account for both the force that causes the planets to orbit the Sun - as described by Kepler - and the downward force that causes objects to accelerate towards the Earth - as described by Galileo.

5.2.1 Newton’s cannonball thought experiment

In 1728, Newton demonstrated the universality of the force of gravity with his cannonball thought-experiment.[2] Here Newton imagined a cannon on top of a mountain. Without gravity, the cannonball should move in a straight line. If gravity is present, then its path will depend on its velocity. If it’s slow, then it will fall straight down. If it reaches the orbital velocity (discussed in Section 5.3) - where the gravitational force equals the centripetal force - then it will orbit the Earth in a circle or ellipse. If it’s faster than the escape velocity - when the kinetic energy is equal to the gravitational potential energy (discussed in Chapter 14) - then it will leave the Earth’s orbit.

Figure 5.5 |

A cannonball travels further the higher its velocity. Here, a higher velocity is designated a higher letter of the alphabet. When the cannonball reaches orbital velocity (C), it falls continuously. It doesn’t hit the ground because the surface of the Earth curves away at the same rate. At higher velocities than this (D), it orbits in an ellipse. When it reaches the escape velocity (E), it never falls and leaves the Earth’s orbit. |

5.3 The mass of the Sun and planets

For objects in circular orbits, the centripetal force (Fc) is equal to the force of gravity. The centripetal force is the force that causes rotating objects to move in a circle, this can happen, for example, if you swing a yo-yo around.

| Fc = mac | (5.5) |

| Fc = mv2r | (5.6) |

Here, ac is centripetal acceleration (discussed in Chapter 3).

The Earth's orbit is nearly circular, and so the mass of an object like the Earth (m1) can be determined if you know how far away it is from the thing it's orbiting (r e.g. the distance between the Earth and the Sun), how long it takes to make one orbit (P e.g. one year), and the mass of the thing it’s orbiting (m2 e.g. the mass of the Sun).

| Centripetal force | = | m1v2r | (5.7) |

| Gravitational force | = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.8) |

| m1v2r | = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.9) |

v = dΔt, where the time period (Δt) is the period of one orbit (P) and distance is the circumference of a circle (2πr) giving,

| m1(2πr)2rP2 | = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.10) | |

| and so | P2 = (2π)2r3Gm2 | and | m2 = (2π)2r3GP2 | (5.11) |

This equation assumes that m1 is orbiting around m2. In reality, both m1 and m2 orbit the centre of mass between the two objects. This is Kepler’s first law (discussed in Chapter 3), which states that ‘the orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci’.

The two masses balance like objects on a seesaw, a type of lever (discussed in Chapter 4), and just like a lever in balance, the torques on each side are equal so that m1g d1 = m2g d2. This is shown in Figures 5.6 and 5.7.

Here d1 is the distance between m1 and the pivot - the centre of mass - and d2 is the distance between m2 and the centre of mass. The distance, in this case, is equal to the radius of each circle around the centre of mass, and so d1 = r1 and d2 = r2. Finally, as shown in Section 5.4, g is the same for each object, giving,

| m1r1 = m2r2 | (5.12) |

If m1 = m2, then the two masses will balance - i.e. remain in a stable orbit - if they are an equal distance from the centre, and so r1 = r2. If m2 is twice the mass of m1, then it will have to be placed half the distance from the pivot - the centre of mass - in order to balance. When m2 is far greater than m1, then m2 will be placed so close to the centre of mass, that the centre will be within its radius.

This would be the case for the Earth and Sun, however, for objects in the Solar System, there are more than just two objects to balance. Many objects are in a stable orbit around the Sun, and the most massive of these is Jupiter. The mass of Jupiter means that the centre of mass in the Solar System is actually about 700,000 km from the centre of the Sun. This is about the same distance as the radius of the Sun, as shown in Figure 5.6.

Mass and distance

Figure 5.6 |

Objects in a stable orbit around a centre of mass act like a lever in balance. |

Figure 5.7 |

The centripetal force causes both m1 and m2 to accelerate towards the centre of mass, represented by the red cross. |

The gravitational force only depends on the distance between m1 and m2. It’s not affected by where the centre of mass is, and so the equation remains the same, but the centripetal force is different. The centripetal force pulls both m1 and m2 towards the centre of mass, and so,

| P2 = (2π)2r1r2Gm2 | and | m2 = (2π)2r1r2GP2 | (5.13) |

Just as with a lever in balance, m1r1 = m2r2. This can be rearranged to show that r1 = r m2m1+m2 and so,

| P2 = (2π)2r3G(m1+m2) | and | m1+m2 = (2π)2r3GP2 | (5.14) |

This is known as Newton’s derivation of Kepler’s third law.

All of this means that if you know the time it takes for an object to complete one orbit of another, and the distance between the two objects, then you can work out the total sum of their masses.[3][4]

5.4 Mass and acceleration

Newton’s law of gravitation shows that objects with different masses fall at the same rate when combined with his second law of motion. This is because an object’s acceleration due to the force of gravity only depends on the mass of the object that is pulling it.

| Force | = | m1a | (5.15) |

| Gravitational force | = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.16) |

| m1a | = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.17) |

| a | = | Gm2r2 | (5.18) |

Here, m1 is the mass of the less massive object (a feather or hammer in this case) and m2 is the mass of the more massive object (a planet or moon). This shows that very heavy and very light objects will fall at the same rate if they are dropped in the same place and there is no air resistance.

This was proven in 1971 when Apollo 15 astronaut Commander David Scott dropped a feather and hammer at the same time on the Moon. The Moon has no atmosphere to create air resistance, and so they fell at the same rate, reaching the Moon’s surface at the same time.

The acceleration due to the force of gravity is referred to as g.

| g = Gm2r2 | (5.19) |

The law of pendulums (discussed in Chapter 2) can be derived by putting g = Gm2r2 into P2 = (2π)2r3Gm2.

| If g = Gm2r2 and P2 = (2π)2r3Gm2 then P = 2π √rg. | (5.20) |

Here, P is the period. The period of a pendulum and the period of a planet are both equal to the time it takes for them to cover a distance equal to the circumference of one full circle - 2πr. r is the radius of this circle, equal to the length of the pendulum.

Figure 5.8 |

The Apollo 15 Lunar Module on the Moon in 1971. |

5.4.1 The mass of the Earth

The mass of the Earth was first determined by the British natural philosopher Henry Cavendish in 1797.[4] g = Gmr2 (where m = m2), and so,

| Mass of the Earth = gr2G | (5.21) |

The radius of the Earth can be derived from the circumference, which was first measured by Eratosthenes (discussed in Chapter 3).[5]

On Earth, g = 9.8 ms-2. Galileo showed how you could derive g in the 16th century by measuring the acceleration of falling objects (discussed in Chapter 4)[6] and, in about 1666, Robert Hooke suggested that a pendulum could be used to measure the acceleration due to gravity (discussed in Chapter 2).

Cavendish showed how G could be determined by measuring the gravitational force between two objects of known masses in a laboratory, using an instrument known as a torsion balance. Once Cavendish could compare the different forces exerted by different masses, he could calculate G, and use it to work out the mass of other objects.

Cavendish found that G = 6.674 × 10-11 m3 kg-1 s-2 when everything is measured in units of metres, kilograms, and seconds. The mass of the Earth was calculated to be about 5.97 × 1024 kg (this is about six million, billion, billion), the value accepted today.

5.4.2 Acceleration due to gravity on Earth

The Earth has a mass of about 5.97 × 1024 kg, and so the acceleration due to gravity on the surface of the Earth, about 6,371,000 m from its centre, is,

| g on the surface of the Earth | = | Gmr2 | (5.22) |

| = | 6.674×10-11 × 5.97×10246,371,0002 | ||

| = | 9.8 ms-2 | ||

| = | 1 g |

This number gets rapidly lower the further you get from the surface of the Earth, by the time you are about 400 km away (which is roughly the distance from London to Paris), it falls by about 10%. At 4000 km, it falls by about 60%, and by the time you get to the Moon, which is 384,400 km away, it has fallen by over 99.9%.

This number gets rapidly higher the closer you get to the centre of the Earth. The fact that it’s infinite at a radius of 0 is indicative of our lack of understanding about how physics works at very small lengths (discussed in Book II).

The force of gravity 10 cm from the centre of the Earth is,

| g 10 cm from the centre of the Earth | = | 6.674×10-11 × 5.97×10240.12 | (5.23) |

| = | 4×1016 ms-2 | ||

| = | 4×1015 g |

If you could tunnel to the centre of the Earth, however, then you would not feel this force. At the centre of the Earth, the gravity of the Earth would be accelerating you equally in all directions, and so you would feel weightless.[7]

5.4.3 Acceleration due to gravity on an asteroid

All objects with strong enough gravitational fields become approximately spherical. This is because the surface is pulled inwards equally in all directions. Objects made of rock tend to be spherical if they have a mass over about 1020 kg, which is the mass of some asteroids.[8] This is about 60,000 times less massive than the Earth and produces objects with a radius of about 300 km.[9]

| g on an asteroid | = | 6.674×10-11 × 1020300,0002 | (5.24) |

| = | 0.074 ms-2 | ||

| = | 0.0076 g |

5.4.4 Acceleration due to gravity on the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) orbits the Earth from about 400 km away,[10] and so,

| g on the International Space Station | = | 6.674×10-11 × 5.97×1024(6,371,000 + 400,000)2 | (5.25) |

| = | 8.7 ms-2 | ||

| = | 0.9 g |

This is 90% of the gravity on the surface of the Earth, which means that people on the ISS do not appear to be weightless because of their distance from the Earth. Instead, they appear weightless because the ISS accelerates towards the Earth at about 8.7 ms-2, which means that it’s in ‘free-fall’.

Objects in free-fall are accelerating towards the Earth at the same rate as they are accelerated by gravity. If there is no drag from the atmosphere, then objects in free-fall act as if they are weightless. You do not feel this drag if you are in an enclosed space, like a space station or an aeroplane, and so you can experience weightlessness on a zero-G flight. Here, an aeroplane accelerates you towards the Earth at 9.8 about ms-2, and so the floor appears to fall away from you at the same rate as you are pulled towards it by gravity. This makes it appear as if you are hovering above a stationary floor.

Objects in orbit, like the ISS, constantly fall towards the surface of the Earth without ever reaching the ground. This is because the surface is spherical, and so falling away at the same rate.

5.4.5 Mass and weight

You may feel weightless when in free-fall, but you still have the same mass.

In physics, mass is a fundamental property that particles have (discussed in Book II). A person’s mass is the sum of the mass of all the particles in their body, and so their body mass only changes if they add or remove some of these particles.

Weight is simply another name for the gravitational force described by Newton’s law of universal gravitation, and ‘apparent weight’ is the force you feel due to your total acceleration.

| Weight | = | Force of gravity | (5.26) |

| = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.27) |

Weight can also be described using Newton’s second law F = ma.

| Weight | = | Mass × Acceleration due to gravity | (5.28) |

| = | m1 × g | (5.29) | |

| = | Gm1m2r2 | (5.30) |

Here, m1 and m2 are interchangeable. The weight of a 60 kg person on the surface of the Earth is,

| Weight | = | 60 kg × 9.8 ms-2 | (5.31) |

| = | 589 kg ms-2 | ||

| = | 589 N |

This means that the Earth exerts a 589 N force on a 60 kg person due to its gravitational field. If the two masses were reversed, however, and you calculated the force on the Earth caused by the gravitational field of a 60 kg person, then the equation would remain the same. This means a 60 kg person exerts a 589 N force on the Earth due to their gravitational field.

Another way of saying this is that the weight of the Earth caused by its acceleration under the gravitational field of an object is the same as the weight of that object.

What is 1 kg?

The gram was defined in 1795 as the mass of one cubic centimetre of water at the melting point of water,[11] however the terms ‘mass’ and ‘weight’ were often used interchangeably when referring to objects on Earth until the late 19th century.

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) formed in 1875 and representatives from different countries met in Paris to develop a common international measuring system, known as the metric system.[12] In 1889, the CGPM created an object out of a platinum-iridium alloy that was 1000 times the mass of a gram. This is a kilogram, where kilo refers to 1000.[13] The CGPM declared that from then on, the mass of a kilogram in the metric system would refer to the mass of this object, and copies were taken to each member country.

In 1901, the CGPM confirmed that the kilogram is a unit of mass, not weight. Weight is measured in newtons (N), the same unit as other forces.[13]

5.5 Mass and energy

As shown in Chapter 4, the amount of energy transferred (ΔE) by a force (F) is equal to the force multiplied by the distance the force acts over.

| ΔE = Fd | (5.32) |

5.5.1 Gravitational potential energy

For gravitational potential energy (GPE),

| GPE | = | Fd | (5.33) |

| = | Gm1m2r2r | (5.34) | |

| = | Gm1m2r | (5.35) |

This is the same as British engineer William Rankine’s concept of potential energy, which is the energy that is needed to keep an object from falling from a height (discussed in Chapter 4).

| GPE | = | m1gh | (5.36) |

| = | Weight × Distance | ||

| = | m1Gm2r2r | (5.37) | |

| = | Gm1m2r | (5.38) |

Here h is height, which is equal to the radius (r).

5.5.2 Kinetic energy

For kinetic energy,

| KE = Fd | (5.39) |

| KE = mad | (5.40) |

This is the same as Coriolis’ equation for kinetic energy (discussed in Chapter 4).

| v | = | dt | (5.41) | |

| = | vinitial + vfinal2 | |||

| and | ||||

| a | = | Δvt | (5.42) | |

| = | vfinal - vinitialt | |||

| giving | ||||

| t | = | vfinal - vinitiala | (5.43) | |

| so that | ||||

| d | = | (vinitial + vfinal)(vfinal - vinitial)2a | (5.44) | |

| and | ||||

| ad | = | 12 (vfinal2 - vinitial2) | (5.45) |

Kinetic energy only applies to objects that are moving, and so vinitial is always 0, giving,

| ad = 12 v2 | (5.46) |

where v = vfinal. Finally, this gives,

| KE = 12 mv2 | (5.47) |

5.6 Newton and absolute space

Newton believed that space and time must be absolute. This means they provide a background in which things take place and would continue to exist even if there were no objects in the universe.[14][15]

This is known as spacetime substantivalism because it implies that space is composed of some kind of pseudo-substance, like Aristotle’s aether (discussed in Chapter 4).

5.6.1 Leibniz and relative space

Gottfried Leibniz accepted that the law of gravitation could be universalized, but objected to Newton’s concept of absolute space. Firstly, he argued that Galileo had shown there’s no such thing as absolute velocity, and so there can’t be any such thing as absolute space, from which it’s derived. Secondly, Leibniz objected to Newton’s description of absolute space as a kind of physical entity because it has no causal powers or independent existence. Leibniz claimed that space is purely a mental entity.[16,17]

The view that space only exists when physical objects are present is known as relationism. Relationism can be countered by the idea that although there is no absolute velocity, there is absolute acceleration, and absolute space can be derived from this.[18]

This argument was reassessed in the first half of the 20th century, after the publication of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity[19] (discussed in Chapter 8).

5.6.2 Olbers’ paradox

Newton’s infinite, eternal, universe posed problems for astronomers as well as philosophers. In 1720, Edmond Halley stated that if the universe is eternal, and the stars are infinitely old, then the sky should be as bright as the surface of the Sun in all directions.[20,21] This is because the starlight from an infinite amount of stars would have reached us by now, filling every part of the sky.

This view was first considered by the English astronomer Thomas Digges in the 16th century, and then by Kepler, the German natural philosopher Otto von Guericke, the French natural philosopher Bernard de Fontenelle, and Christiaan Huygens.[22] It was popularised by the German astronomer Heinrich Olbers in 1823 and is known as Olbers’ paradox.[23] Olbers’ paradox was not resolved until the American astronomer Edwin Hubble provided evidence for the big bang in the first half of the 20th century (discussed in Chapter 9).

5.7 The precession of Mercury

Newton’s theory was first questioned in 1859 when Urbain Le Verrier showed that Mercury’s orbit could not be explained using Newton’s equations.[24]

Mercury does not form a closed ellipse when it orbits the Sun. Instead, the ellipse rotates. This sort of movement is known as precession and it was later explained by Einstein’s theory of general relativity (discussed in Chapter 8).

Figure 5.9 |

The precession of Mercury’s orbit. |